|

It’s

a terrible pourer, it spills tea everywhere.” Jack Hanlon is holding up

an undistinguished brown teapot. Like everything else in this tiny,

windowless room —measuring just 13 feet by 16 feet or so—the teapot is

not for appearance or entertaining or even utility, but for basic

survival. It would, in theory, be able to provide cups of tea for up to

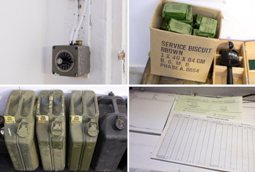

three weeks. Jerry cans of water are lined up along one wall, the

cupboard is rammed full of cans, and narrow bunk beds, complete with

gray blankets that look as though they were made primarily to be itchy,

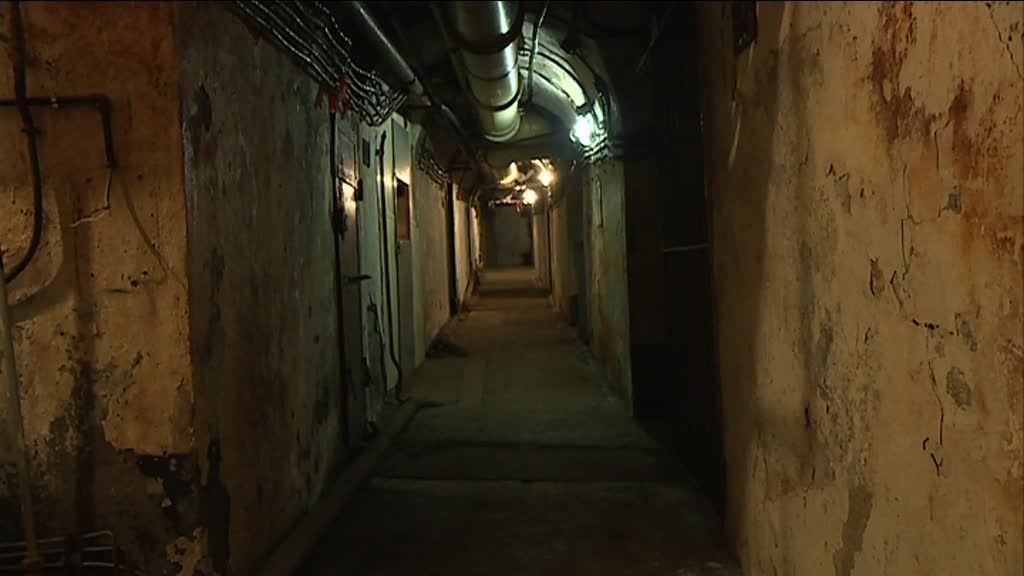

sit in the corner.We’re standing in a room buried 10 feet below the

North Yorkshire moors in northeast England, near the village of

Castleton.

The wind howls over the hatch above our heads as Hanlon—no

expert, just an enthusiast—describes how the room would have been used,

as an outpost of English civility and resourcefulness in the face of a

nuclear attack. This bunker is one of hundreds just like it, scattered

across the country.

They’re no longer in use, having been decommissioned

for decades, but they’re a nationwide network of relics of fear—a fear

that seems never to have left.

Today the “Doomsday Clock,”

maintained by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, is just two minutes

from midnight—the closest it’s been to nuclear annihilation since the

height of Cold War in 1953. If, as UN Secretary-General António Guterres

declared in April 2018, “the Cold War is back with a vengeance,” our old

monuments to precaution, paranoia, and practicality take on a new,

chilling life.

We’re not privy to our governments’ current top-secret

contingency plans, but these bunkers provide a glimpse of the difficult,

high-level decisions and calculated sacrifices that were oncemade, and

how both officials and regular people corralled existential fear with

work and routine. At 23 years old, Hanlon never knew the Cold War

first-hand, but he has always been fascinated with the period, and is

perhaps a little wistful that he missed it. The quietly unassuming

millennial has worked various jobs, most recently as an undertaker, but

he is defined by his hobbies—campanology (the art and practice of

bell-ringing) and restoring Cold War bunkers.

His gritty determination

has earned him the respect of many former military and volunteer

officers from the period, some of whom have donated old equipment. Even

vandals who took aim at the bunkers have not been an obstacle—he

encouraged them to volunteer with the restoration work, and a couple of

them are still involved. Today, the fresh coat of khaki green paint on

the bunker entrance at Castleton, and the neat post-and-rail fence

around the site, just hint at the hard graft, skill, and attention to

detail that made this living museum piece.

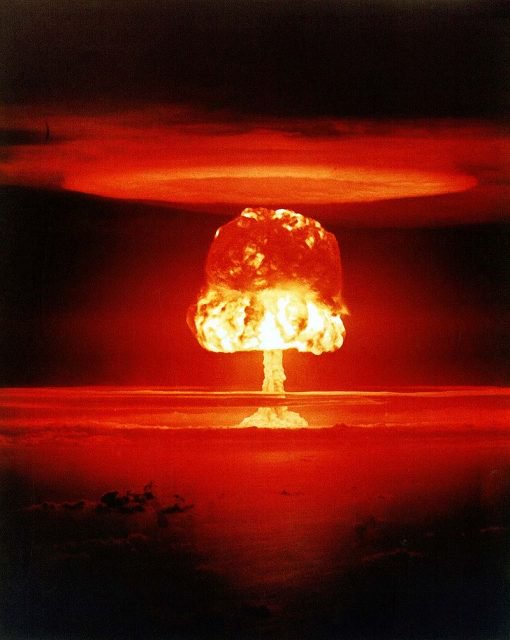

The term “Cold War” is attributed

to a 1945 article written by George Orwell to describe a nuclear

stalemate between “two or three monstrous super-states, each possessed

of a weapon by which millions of people can be wiped out in a few

seconds.” Only the United States had the bomb at that point, but Orwell

saw where things were going, and by the 1950s his prediction had come to

pass. So it was that in 1955, the British Ministry of Defence

commissioned a top-secret report (declassified in 2002) to get a sense

of what nuclear annihilation might look like. The Strath Report, as it

was called, concluded that a Soviet nighttime attack with 10 hydrogen

bombs would kill 12 million people (a third of the population at that

time) and seriously injure another four million. Food and water would be

contaminated, industry shut down, and the National Health Service

utterly overwhelmed.

There are, in such a case, bad options and worse

options, but doing nothing, it was decided, was no option. So the

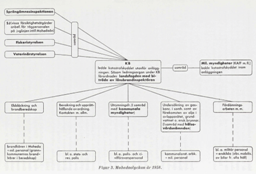

kingdom invested in bunkers. A network designed to protect as many

people as possible was estimated to cost £1.25 billion (equivalent to

£30 billion today), and the government decided this was prohibitive. So

they prioritized a network of smaller underground facilities that

emphasized information, communication, and function after a nuclear

attack. Over the next few years, more than 1,500 holes were blasted into

the ground, from Cornwall to Shetland, and then a standard concrete

bunker was built in each one. These were to be the “eyes and ears” of

the country, and the people who manned them tasked with sending data to

a network of 29 larger regional headquarters, where they would be

collated and used to understand where blasts had occurred, the power of

the weapons, and possible fallout patterns.

The information could then

be shared with military and civilian authorities to help them plan their

responses.

These were not, however, military

installations to be manned at all times. Rather, the government

recruited a network of 10,000 volunteer civilians, known as the Royal

Observer Corps (ROC), which gathered weekly for training at their

respective bunkers.

During periods of rising tension—such as during the

Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962—volunteers were expected to drop their

lives, leave their families, and head to the bunkers, where they would

be organized into three-person shifts. If a nuclear strike occurred, the

entrance hatch would be sealed and it would more or less stay that way

for three weeks. “We knew that psychologically this job would be

immensely difficult, particularly in the full knowledge of what our

families were likely to be facing, just a few miles away,” says Tim

Kitching, who served as an ROC officer during the 1980s. The network was

activated in the late 1950s and was in continuous use until 1991, when

nuclear tensions eased.

The bunkers, which were built on both public and

private land, were released into the wild. Today the majority has been

demolished, or simply left to flood and rot. But two of these bunkers—Castleton

and another nearby called Chop Gate—escaped this fate, thanks to one

Jack Hanlon.

The village of Castleton nestles

into an alcove in one of England’s bleakest and most remote regions.

Above the village an icy wind rips across the landscape, tearing over

sturdy heather shrubs and sending the native red grouse scurrying for

cover.

This is where, just 20 miles from Fylingdales—a key military

target and one of the 30 or so radar stations tasked with watching the

skies and providing the country with a four-minute warning of impending

missile attack—12 dedicated ROC volunteers trained and met, and where

they would have gone had the worst come to pass.

After driving a

half-mile up the steep hill out of Castleton, Hanlon pulls over where

the moorland plateau begins. In steep glacial valleys off each side of

the plateau are marginal pastures enclosed by traditional dry-stone

walls. Hanlon and I stomp up a short grassy track to find the timeless

view interrupted by something distinctly modern.

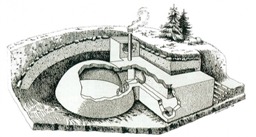

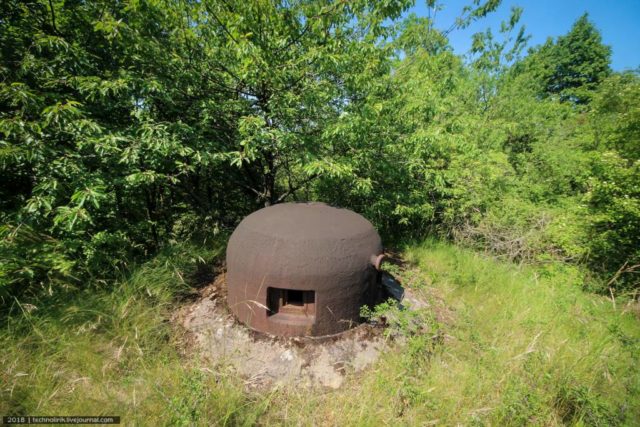

A small hummocky

enclosure emerges from the heather, with a couple of small, angular

concrete structures in the middle.

A black metal tube like a submarine

periscope sprouts incongruously from the ground.

“I first came across this when I

was 14,” Hanlon explains.

“The hatch had been ripped off and the

interior was flooded. I realized it was too big a project for me to

tackle at that time, but it stuck in my mind.” Some years later he also

came across the neighboring Chop Gate bunker and met the owner of the

land it was on, a former ROC officer who used to work at it.

With the

officer’s blessing, Hanlon started to restore Chop Gate.

Soon after, he

returned to Castleton and boldly approached the landowner —it is on the

Danby Estate, owned by Richard Henry Dawnay, the 12th Viscount Downe—for

permission. His work at Chop Gate convinced the viscount that Hanlon was

up to the task. Hanlon undoes three padlocks and heaves open the

blast-proof hatch to reveal a dark hole, roughly two feet square. A

ladder leads into the gloom. We climb gingerly down and step off 15 feet

below the surface.

Claustrophobia sets in quickly, with only a small

square of daylight above, but Hanlon’s presence is oddly reassuring. He

feels official— clean-shaven and dressed in heavy work boots, a high-vis

waterproof jacket, and warm wooly hat—and exudes an unruffled air of

capable competence.

My flashlight reveals a tiny

vestibule off the entrance shaft containing a chemical toilet. To my

left is a darkened doorway. Hanlon flicks on a light, casting the room

in a dim orange glow. There’s a ticking noise. The lights are on a timer

to conserve precious battery power.

Fixing the lights was one of the

first jobs Hanlon tackled when he started work on the Castleton bunker

in earnest in April 2017. “We had to remove 300 liters of water first,

using a bucket and a pulley,” he says. With a team of practical and

handy friends, Hanlon prioritized electricity and used fans on

full-throttle to get the place dry. He is not the boasting type, but the

before-and-after pictures are remarkable, and the wide range of skills

and knowledge required to bring this place back to its original state

and function is evident. Former ROC officers—many of whom have advised

Hanlon on details and shared old photos, documents, and inventory lists—delight

in visiting for a trip down memory lane.

Along the long wall to the left

of the entrance are two canvas chairs neatly tucked under a plain wooden

table. A small mirror is propped on a shelf above—a rare concession to

vanity. On the table, neat piles of forms lie ready for the

documentation of weather observations, radiation levels, and whatever

other details the volunteers could glean about the location of the blast.

At the far end of the room, the metalframed bunk beds take up the entire

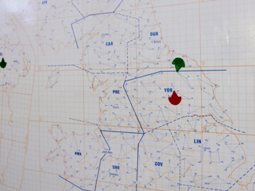

width. A map showing the network of bunkers across the country and

charts to aid cloud identification line one wall.

Many of the pieces of period

equipment have been donated by ex-ROC officers and are testaments to the

power of social media. Hanlon’s Facebook page for the bunker has more

than 450 followers, and he has another for Chop Gate with 400 as well.

Meanwhile, more than 600 showed an interest in his first open day, when

the public was invited to visit. “We had to take bookings as there was

no way we could manage 600 people in one day!” he says. Discussions on

the page have inspired locals to get involved, and resulted in generous

donations of both equipment and specialist knowledge. Some bunkers were

sited in towns or cities, but Hanlon’s are rather remote. Here, the ROC

volunteers were most likely to have been called to duty via phone or

radio bulletin. If attack was thought to be imminent, one of their first

jobs upon arrival would have been to alert the local population with a

hand-cranked siren, just like the ones used during air raids in World

War II. The other two volunteers would prep the “Ground Zero Indicator”—an

instrument that sat above ground. The device used the same principle as

a pinhole camera, only it had four holes, one corresponding to each

compass point. The bomb blast would sear an image onto light-sensitive

paper, and the location and size of the resulting marks could indicate

its height and direction. “The big problem,” says Hanlon, “was that one

of the volunteers had to go outside after the blast, potentially

exposing themselves to the radiation, to collect the paper.” But this

vital information was worth the risk, and the volunteers were expected

to communicate it to the regional headquarters at first opportunity. A

regional headquarters could then plot a number of ground-zero

measurements to determine the power of the weapon, where it detonated,

and whether it was an air or ground burst (ground bursts produce far

more residual radiation from their fallout). The other essential

instrument they operated was the “Bomb Power Indicator,” which consisted

of a pipe that connected the surface with the interior of the shelter.

Inside, a small set of bellows was attached to the end, which would

expand as air rushed in from the blast. The bellows moved a needle,

which would indicate the pressure produced by the blast wave—another

critical piece of information. The three observers would then be

expected to settle into a pattern of regular readings. Exterior

radiation levels could be measured safely from inside, using a “Fixed

Survey Meter,” a small console on the desk connected to a detector above,

but further meteorological measurements required more trips outside, to

record the wind speed, direction, and cloud type. The original Fixed

Survey Meter from the Castleton bunker disappeared long ago, but Hanlon

went to enormous lengths to find a replacement. “I heard about a Fixed

Survey Meter in a flooded bunker on a remote Scottish island, so I

traveled up there, pumped the bunker out, and went down to retrieve it,”

he says. He traveled up and down the country and scoured eBay to find

period- orrect equipment, and took care to renovate and repair what he

found using the same materials and equipment as would have been used

when the bunkers were in service. “I’ve always been interested in

history and I’m a determined kind of person,” he says, with

characteristic understatement. “When I first came across photos of these

bunkers online I just knew I had to go and find out more.”

Thanks to Hanlon’s efforts, it is

now possible to imagine how it might have felt to live down here,

isolated and afraid, while a nuclear war may or may not have been raging

overhead. Deep in the cupboard is a small tin of Tommy’s Cooking Fuel,

solid fuel that could be used to heat up the contents of a mess tin.

Such a moment of gathering to eat baked beans and share a pot of tea

would have served as a vital focal point for the bunker inhabitants, a

way of creating a routine and distinguishing the hours in the absence of

normal day-night cycles. Despite having somewhat better shelter than

most of the general population, the nhabitants of these bunkers knew

that their chances of survival would be still relatively slim. As the

howling draft coming down the ventilation shaft into the Castleton

bunker demonstrates, the protection the bunkers could offer was modest

at best. Furthermore, the volunteers were expected to leave for

measurements, so longterm safety was clearly not a goal. Despite feeling

confined, I am reassured by the organization and purpose I see around

me. Even if it didn’t offer the greatest protection, I can imagine that

useful activity would feel superior than merely awaiting my fate. Over a

steaming coffee in the city of York, former ROC officer Tim Kitching

explains the government’s Cold War strategy to me. “The risk of losing

observers [due to radiation exposure] was outweighed by the gain in

information from the Ground Zero Indicator readings,” he says. Certainly

the bunkers were intended to aid survival, and support the continuance

of some form of governance after a nuclear exchange, but their primary

role was as a passive deterrent. “This warning and monitoring system was

designed to support our own forces in surviving a first strike in

sufficient numbers to strike back, thereby deterring any aggressor in

making first use, knowing that there was a degree of certainty that they

would be hit back,” he says.

Kitching, who is smartly turned

out in creased slacks, and has an organized and efficient air about him,

was motivated to serve in the ROC out of a desire to contribute to the

defense of the country. “Being ready to do what we were training to do

was simply part of the country’s insurance policy,” he says. Kitching

was confident that the system would have worked well. “Within the Corps

there was multiple ‘redundancy’ built in throughout,” he explains. “So,

for example, posts had a complement of 10, but only three were needed

for an operational crew.” The overall simplicity enabled them to live

off the grid—without piped-in gas, electricity, or water. There was,

however, one link—a weak link—between the bunker and the rest of the

world, its overground telephone connection, which was used to transmit

information between monitoring posts and to the regional headquarters.

The wooden poles and looping wires that connected bunkers in the early

days of the network would almost certainly have been knocked over by a

nuclear blast, which would have left the bunkers isolated and the

precious observations completely useless. By the 1980s, the British

Government lessened this risk by investing in private, underground

telephone wires between bunkers. Furthermore, monitoring posts were

grouped into clusters of three or four, each about 15 miles apart and

linked by telephone. One bunker in each cluster served as a “master

post,” equipped with radio communications to back up the telephone

system. Castleton was one of the lucky bunkers, and held a radio and

antenna. In the Castleton bunker, Hanlon points out the bright yellow

“Tele-Talk” loudspeaker telephone on the desk, and the prized VHF radio

set on a small shelf above. With luck, Castleton would have been able to

communicate its observations, and hopefully those of the other bunkers

in its cluster (Hinderwell and Goathland, in this case), to the regional

headquarters, 50 miles away in the historic city of Durham.

The Durham regional headquarters

no longer exists, so instead I travel south to York to see the only one

of the 29 regional headquarters to have been preserved. The York Cold

War Bunker is one of the city’s best kept secrets, situated out in the

suburbs, on a nondescript street, lined with ordinary houses and neatly

mowed lawns.

At the end of a cul-de-sac, however, is a distinctly

extraordinary sight. A rectangular grassy mound rears up to around 10

feet above street level.

A flight of concrete steps leads up the mound

to a flat-roofed, boxy green building. Locals call it the “Aztec Temple.”

When it was in use, this building was hidden in a hollow, surrounded by

an orchard, hundreds of yards from a main road. Since 2006, English

Heritage has operated it as an unusual tourist attraction.

The visible

structure is just the top level of a three-story building hidden in the

hill. The lower two levels are further covered in three layers of

asphalt, and then at least three feet of earth—all to protect against a

blast, heat, and radiation.

Twenty steps bring me to the top

of the mound and the green concrete box.

A strange cylindrical structure

like an outsized chimney pokes out of the flat roof, and a radio aerial

bristles to my right. A small wooden noticeboard just inside the door

informs me that the “attack state” is “black.” Once inside the door, I

pass through an airlock— two rubber-sealed, gas-proof doors—and then

descend stairs into the heart of the bunker. It is around 4,000 square

feet, containing a kitchen, canteen, dormitories, plant room, generator

room, telephone exchange, and officers’ room, with a large gallery

overlooking the operations room, another level down.

This bunker is an

entirely different beast than the drafty underground cell in Castleton.

“One-hundred and twenty volunteers and four paid officers were trained

up to use this bunker,” says Jake Tatman, who works behind the scenes

there. “If nuclear war was likely you’d have everyone working on shifts

with 60 staff manning the bunker at any one time.” If a nuclear strike

occurred, the door would be locked and the crew inside would prepare for

30 days of tracking radiation and weather, and collating and plotting

measurements from the surrounding posts. And just like at Castleton, one

poor sod would have to go outside after the blast to retrieve the

light-sensitive paper from the Ground Zero Indicator. He or she, however,

would have had the added luxury of a shower, to help wash off some

radioactive particles.

This bunker also would have had a

few specialists.

“During an emergency it was essential that the bunker

had at least one engineer, capable of keeping the generator and air

conditioning system going,” explains Tatman, outside the diesel

generator room.

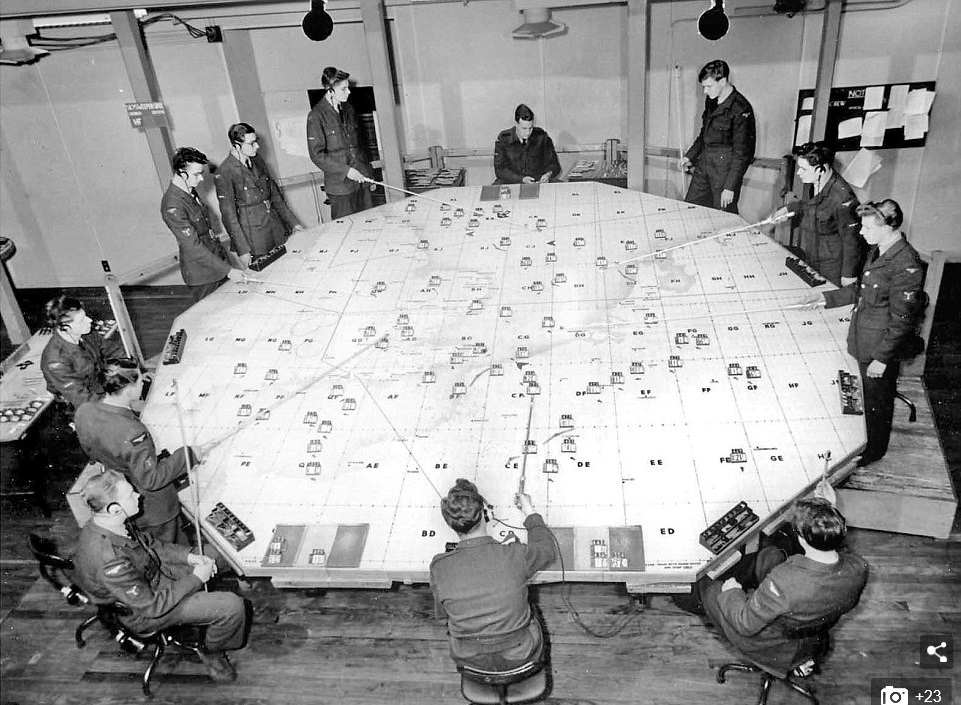

In the gallery, a team of specialist plotters would have

sat at a row of desks, listening for information from outlying bunkers

and putting it up on rotating Perspex display boards, which could be

swiveled around to be viewed by still more specialists in operations

below. Data would be plotted on the triangulation table, and the

location of blasts would then be transferred to four large maps on the

wall: the current situation, the cumulative situation, the United

Kingdom situation, and the European situation. Meanwhile, on the

opposite side of the gallery, a group of tellers would pass this

information to other group headquarters, as well as government and

military facilities.

It is through this process, ideally, that the

contributions of volunteers at local bunkers like Castleton would make

their way into the corridors of power, where the difficult decisions

were to be made.

At least in theory. In practice,

the York bunker might not have survived the first day. “York was the hub

of the railway industry and it had four RAF [Royal Air Force] bases, so

it would have been a big target,” says Tatman. “The chances are that

this bunker wouldn’t exist at all after a nuclear attack.” The

volunteers running the more remote observation posts might survive the

initial attack, only to have to fend for themselves. With all of this in

mind, utility, survival, and maintenance of a functional society were

hopeful, secondary goals for the bunkers. The network was, by design,

one of Cold War Britain’s worst-kept secrets, at home and abroad. The

very existence of these bunkers, and the willingness of thousands of

volunteers to train to defend their country, could have played a role in

preventing a nuclear strike from occurring in the first place. And today,

as tensions rise again, it feels like we need to rediscover something of

the calm and stoicism that these bunkers were built to encourage.

Perhaps we would be more confident if we knew that our friends and

neighbors had our backs.

Throughout the Cold War, this system—of both

bunkers and people—played a significant role in boosting morale and

containing fear. Neither of these things seems particularly possible

today. The restored York and Castleton sites evoke a kind of nostalgia,

for when it at least seemed like ordinary citizens had the power to help

each other, even if it was rather illusory. Teapots that don’t pour

properly and itchy blankets are important comforts when you feel like

there’s a greater purpose to them. |

Mark

41 thermonuclear bomb casing at the

National Museum of the United States Air

Force.

Mark

41 thermonuclear bomb casing at the

National Museum of the United States Air

Force.

.jpg)

.jpg)

There

are enough bomb shelters for just 30 per cent of the population By

Annette Chrysostomou

There

are enough bomb shelters for just 30 per cent of the population By

Annette Chrysostomou

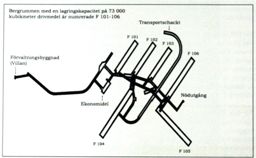

Vid ett av det stora centrallager, närmare bestämt Klintaberget i Moheda, inträffade den 23 juli 1958 en våldsam explosion i berget som kom att beskrivas som “den stora smällen i Moheda”. I berget förvarades drivmedel för såväl flygvapnet, marinen och armén, och innehöll den ödesdigra dagen cirka 14 000 kubikmeter drivmedel (bergets kapacitet var 17 000 kubikmeter).

Vid ett av det stora centrallager, närmare bestämt Klintaberget i Moheda, inträffade den 23 juli 1958 en våldsam explosion i berget som kom att beskrivas som “den stora smällen i Moheda”. I berget förvarades drivmedel för såväl flygvapnet, marinen och armén, och innehöll den ödesdigra dagen cirka 14 000 kubikmeter drivmedel (bergets kapacitet var 17 000 kubikmeter).

.jpg)

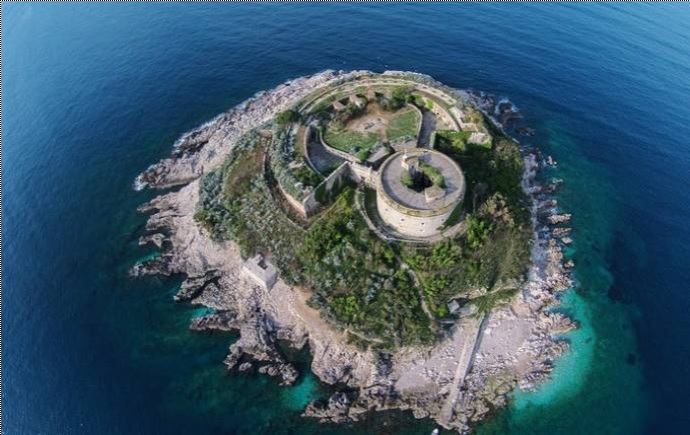

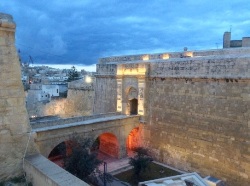

Mdina,

Malta

Mdina,

Malta Fort

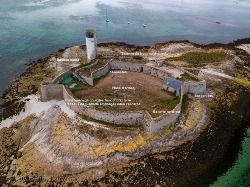

St. Angelo, Malta. By Felix König – CC BY 3.0

Fort

St. Angelo, Malta. By Felix König – CC BY 3.0 View

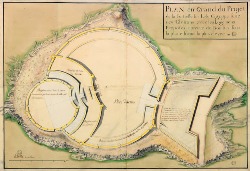

of the Senglea Land Front in c. 1725, with Fort St. Michael in the

centre. By M-A. Benoist – CC BY 4.0

View

of the Senglea Land Front in c. 1725, with Fort St. Michael in the

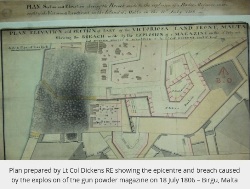

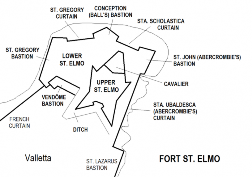

centre. By M-A. Benoist – CC BY 4.0 Map

of Fort St. Elmo in Valleta, Malta – The fort held out for 28 days

during the siege. Only 9 soldiers survived. – Xwejnusgozo CC BY-SA 4.0

Map

of Fort St. Elmo in Valleta, Malta – The fort held out for 28 days

during the siege. Only 9 soldiers survived. – Xwejnusgozo CC BY-SA 4.0