In 1982, a 40-year-old insurance salesman who sold

policies to professional athletes traveled from his home

in Lawrence, Kansas, to New York City on a business

trip. Shortly before he left, Bob Swan, Jr.—the father

of two young daughters, and a man increasingly concerned

about the possibility of a nuclear war between the

United States and the Soviet Union—mentioned to his

then-wife Jane that he had had a dream about a film that

portrayed an American family and a Russian family in the

aftermath of nuclear war and “showed the total absurdity”

of such a war. While he was in New York, Swan attended a

huge march for nuclear disarmament that was

life-changing for him. “When I got back from this

amazing experience,” Swan told me when I visited him at

his home a few months ago, one of the first things his

wife said was: “They announced while you were gone,

they’re going to make that film you dreamed about. They’re

going to film it in Lawrence.”

The television movie The Day After depicted a full-scale

nuclear war and its impacts on people living in and

around Kansas City. It became something of a community

project in picturesque Lawrence, 40 miles west of Kansas

City, where much of the movie was filmed. Thousands of

local residents—including students and faculty from the

University of Kansas—were recruited as extras for the

movie; about 65 of the 80 speaking parts were cast

locally. The use of locals was intentional, because the

moviemakers wanted to show the grim consequences of a

nuclear war for real middle Americans, living in the

real middle of the country. By the time the movie ends,

almost all of the main characters are dead or dying.

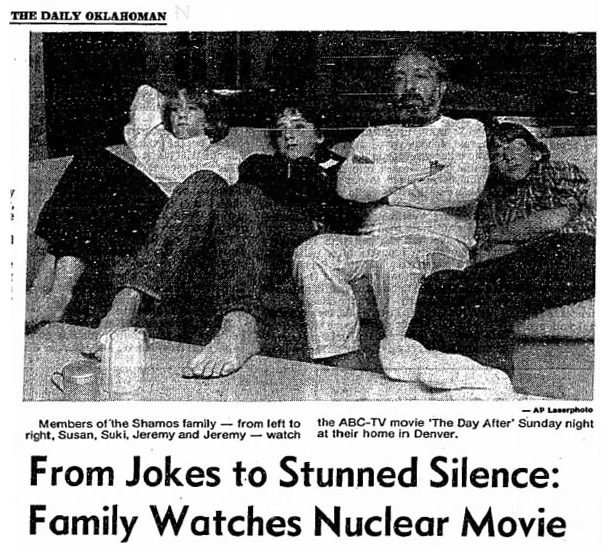

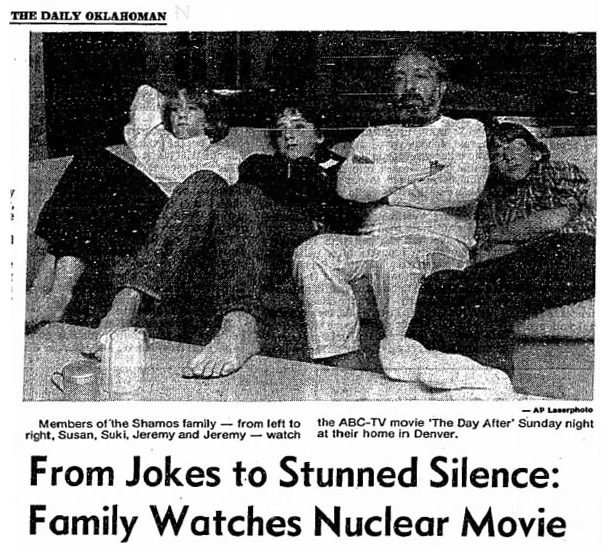

ABC broadcast The Day After on November 20, 1983, with

no commercial breaks during the final hour. More than

100 million people saw it—nearly two-thirds of the total

viewing audience. It remains one of the most-watched

television programs of all time. Brandon Stoddard,

then-president of ABC’s motion picture division, called

it “the most important movie we’ve ever done.” The

Washington Post later described it as “a profound TV

moment.” It was arguably the most effective public

service announcement in history.

“For those of us who live in Lawrence, it was

personal... and it didn’t have a happy ending.”

It was also a turning point for foreign policy.

Thirty-five years ago, the United States and the Soviet

Union were in a nuclear arms race that had taken them to

the brink of war. The Day After was a piercing wakeup

shriek, not just for the general public but also for

then- President Ronald Reagan. Shortly after he saw the

film, Reagan gave a speech saying that he, too, had a

dream: that nuclear weapons would be “banished from the

face of the Earth.” A few years later, Reagan and Soviet

leader Mikhail Gorbachev signed the Intermediate- Range

Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, the first agreement that

provided for the elimination of an entire category of

nuclear weapons. By the late 1990s, American and Russian

leaders had created a stable, treaty-based arms-control

infrastructure and expected it to continue improving

over time.

Now, however, a long era of nuclear restraint appears to

be nearing an end. Tensions between the United States

and Russia have risen to levels not seen in decades.

Alleging treaty violations by Russia, the White House

has announced plans to withdraw from the INF Treaty.

Both countries are moving forward with the enormously

expensive refurbishment of old and development of new

nuclear weapons—a process euphemized as “nuclear

modernization.” Leaders on both sides have made

inflammatory statements, and no serious negotiations

have taken place in recent years.

There are striking parallels between the security

situations today and 35 years ago, with one major

discordance: Today, nuclear weapons are seldom a front-

urner concern, largely being forgotten, underestimated,

or ignored by the American public. The United States

desperately needs a fresh national conversation about

the born-again nuclear arms race—a conversation loud

enough to catch the attention of the White House and the

Kremlin and lead to resumed dialogue. A look back at The

Day After and the role played by ordinary citizens in a

small Midwestern city shows how the risk of nuclear war

took center stage in 1983, and what it would take for

that to happen again in 2018.

A CITY IN ASHES

Aftermath of the nuclear attack on

Lawrence depicted in The Day

After.

In the film, a 12-year-old farm girl named “Joleen” who

has heard an alarming report on the radio asks her

father, “There’s not going be a war, is there?” That

question was “really emotional for me,” says David

Longhurst, who was mayor of Lawrence in 1983 and is now

in his mid-70s. He had a son who was 12 at the time, and

the girl who played “Joleen” was the daughter of close

friends. The Day After had a huge impact on the American

psyche. But, Longhurst says, “for those of us who live

in Lawrence, it had an even greater impact. It was

personal ... and it didn’t have a happy ending.”

In fact, Lawrence—a small city of less than 100,000,

including about 30,000 students at the University of

Kansas, that lies between two rivers and is dotted with

leafy parks and limestone buildings—has a long history

of devastation, followed by repeated resurrection. It

was founded by anti-slavery settlers who hoped that

Kansas would enter the union as a free state. In 1856,

pro-slavery activists led by the county sheriff sacked

the town. They burned down the Free State Hotel, but a

prominent abolitionist named Col. Shalor Eldridge

rebuilt the hotel and named it after himself. The hotel,

in the midst of another renovation, is where I met

Longhurst a few months ago. A part- wner of the hotel,

he showed me its Crystal Ballroom and Big 6 Bar (which

dates back to the collegiate sports conference of the

speakeasy era).

A much bloodier raid followed in 1863, when Confederate

guerillas led by William Quantrill attacked Lawrence,

massacring more than 150 men and boys and burning down

hundreds of homes and businesses, including the Eldridge

Hotel. The town rebuilt, and since the 1860s has adopted

as its symbol a phoenix rising from the ashes. So it was

perhaps fitting that Lawrence was again reduced to ashes—on

film, at least—in 1983.

To turn Lawrence into a war zone, the film’s producers

closed sections of Massachusetts Street (downtown’s

pedestrian-friendly main street, lined with shops and

trees) more than once, blew out the windows of

storefronts, gave buildings a charred makeover, and

littered downtown with ash, debris, and burned-out

vehicles. A few blocks from downtown, the filmmakers

built a tent city to house “refugees” under a bridge on

the banks of the Kansas River, known locally as the Kaw.

Each tent housed a family and some of the possessions

they had presumably taken when they fled from devastated

homes: a doll here, a radio there.

“As

you went from tent to tent, it was like going through a

neighborhood,” recalls Jack Wright, a now-retired

theater professor at the university who became the

casting director for the film’s extras, and whose

stepdaughter—Ellen Anthony—played “Joleen” in the movie.

When I met Wright and his wife Judy (who was an extra in

the movie, and whose hint-of-Texas voice immediately

reminded me of her daughter Ellen’s) at their house in

Lawrence, we looked at magazine clippings and interviews

with Ellen that had taken place in their home 35 years

earlier.

“As

you went from tent to tent, it was like going through a

neighborhood,” recalls Jack Wright, a now-retired

theater professor at the university who became the

casting director for the film’s extras, and whose

stepdaughter—Ellen Anthony—played “Joleen” in the movie.

When I met Wright and his wife Judy (who was an extra in

the movie, and whose hint-of-Texas voice immediately

reminded me of her daughter Ellen’s) at their house in

Lawrence, we looked at magazine clippings and interviews

with Ellen that had taken place in their home 35 years

earlier.

Wright, who is 75 and still has a grade- chool-issued

civil defense helmet in his garage, continues to direct

and act in theater productions, including a one-man show

in which he plays the legendary Kansas newspaper editor

William Allen White. Before he dashed off to a rehearsal,

he told me what it was like being at the university’s

beloved Allen Fieldhouse, home of the Kansas Jayhawks,

in 1983 when the basketball court was transformed into a

“hospice” littered with cots for the victims of

radiation sickness. He remembers that director Nicholas

Meyer told the extras not to look at the camera or

anything else and reminded them that if a nuclear war

had really happened, “nobody would leave this room alive.

You’re on your last legs.” It was silent in the vast

room, and Wright says the moviemakers at that time were

still considering calling the movie Silence in Heaven.

Sometimes, after shooting a scene, the extras talked

about nuclear war and what they would lose, what it

would mean for a small city in the heart of the country.

One of the most haunting lines in the film comes when

John Lithgow, playing a university science professor who

has survived the nuclear blast, speaks into his

shortwave radio: “This is Lawrence. This is Lawrence,

Kansas. Is anybody there? Anybody at all?”

BEYOND IMAGINING

On Columbus Day in 1983, Ronald Reagan was at Camp

David, the wooded presidential retreat in Maryland. That

morning, before he boarded a Marine helicopter to fly

back to the White House, he previewed an ABC

made-for-television movie with the tagline “Beyond

imagining.” The Day After deeply affected Reagan,

himself a product of Hollywood. He wrote in his diary:

“It is powerfully done—all $7 mil. worth. It’s very

effective & left me greatly depressed... My own reaction

was one of our having to do all we can to have a

deterrent & to see there is never a nuclear war.” In an

interview last year, Meyer said Reagan’s official

biographer told him “the only time he saw Ronald Reagan

become upset was after they screened The Day After, and

he just went into a funk.”

On November 18, 1983, two days before the film aired on

network television, Reagan wrote in his diary of “a most

sobering experience” in the Situation Room, where he

received a military briefing “on our complete plan in

the event of a nuclear attack.” In his 1990

autobiography, An American Life, Reagan recalled the

briefing: “Simply put, it was a scenario for a sequence

of events that could lead to the end of civilization as

we knew it. In several ways, the sequence of events

described in the briefing paralleled those in the ABC

movie. Yet there were still some people at the Pentagon

who claimed a nuclear war was ‘winnable.’”

In that same diary entry, Reagan noted that Secretary of

State George Shultz would go on ABC “right after it’s

[sic] big Nuclear bomb film Sunday night. We know it’s

‘anti-nuke’ propaganda but we’re going to take it over &

say it shows why we must keep on doing what we’re doing.”

Two days later, Shultz appeared before the nation and

told ABC News’ Ted Koppel that the film was “a vivid and

dramatic portrayal of the fact that nuclear war is

simply not acceptable,” saying that US nuclear policy

had been successful in preventing such a war. “The only

reason we have nuclear weapons,” Shultz said, “is to see

to it that they aren’t used.” Shultz told Koppel that

the United States had a policy not only of deterrence

but also of weapons reduction—eventually to zero. (Although

ABC and the film’s director were careful to remain

ambiguous about which side started the fictional nuclear

war, insisting that the film was “not political,” The

Day After left no doubt that deterrence had failed.)

After Shultz spoke, Koppel hosted a televised discussion

with a distinguished panel of guests, including former

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, author Elie Wiesel,

publisher William F. Buckley, Jr., astronomer Carl Sagan,

national security expert Lt. Gen. Brent Scowcroft, and

former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. Their

reactions ranged from Buckley’s denunciation of the film

as propaganda “that seeks to debilitate the United

States,” to Sagan’s comment that a real nuclear war

would be even more lethal than depicted in the film

because it would be followed by a nuclear winter.

Whatever their intentions, Reagan and Shultz made little

progress with the Soviets on nuclear weapons until

Gorbachev became General Secretary of the governing

Communist Party in March 1985. Immediately afterward,

Reagan invited him to a summit. They met in Geneva that

November; the meeting was scheduled for 15 minutes but

lasted five hours. The next year, in Reykjavik, they

came very close to agreeing to destroy all their nuclear

weapons, and the director of The Day After received a

telegram from the administration telling him, “Don’t

think your movie didn’t have any part of this, because

it did.” In 1987, the year that The Day After was first

shown on Soviet television, the two leaders reached

agreement on the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces

Treaty. By then, as many as 1 billion people may have

seen the film.

Today, commentators such as Fox News political anchor

Bret Baier and syndicated radio talk-show host Rush

Limbaugh claim to see parallels between presidents

Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump, and between the

Reagan-Gorbachev summit and Trump’s historic summit with

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. Like Reagan, who called

the Soviet Union an “evil empire” in a March 1983

address to the National Association of Evangelicals,

Trump initially responded to North Korea’s nuclear

program with his infamous threat of “fire and fury.”

In the United States and Russia—and now also North Korea—there

is still just one person’s finger on the “nuclear button.”

When Reagan was president, his first-term chief of staff

and other establishment Republicans reportedly feared

that Reagan might get the country into a nuclear war.

Last year, similar concerns among some of Trump’s fellow

Republicans were on public display. Bob Corker, the

Republican chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations

Committee, for example, told the New York Times that

Trump’s reckless threats could put the United States “on

the path to World War III.”

In 1983, an opinion poll found that about half of

Americans thought they would die in a nuclear war.

Although nuclear weapons get a smaller share of press

attention today than in 1983, a Gallup poll conducted

earlier this year reported that Americans fear the

development of nuclear weapons by North Korea more than

any other “critical threat,” and a Washington Post-ABC

News poll found that “about half of Americans are

concerned that President Trump might launch a nuclear

attack without justification.” The Global Risks Report

2018, published in January by the World Economic Forum

and drawn from a survey of the group’s 1,000 members,

warned “the North Korea crisis has arguably brought the

world closer than it has been for decades to the

possible use of nuclear weapons” and has “created

uncertainty about the strength of the norms created by

decades of work to prevent nuclear conflict.”

RISING NUCLEAR TENSIONS: Echoes of 1983

More than 50 years after the Nuclear Non-Proliferation

Treaty declared the intention of 190 nations (including

the United States) “to achieve at the earliest possible

date the cessation of the nuclear arms race,” the United

States and Russia still have enough weapons to destroy

the world many times over—and many of them still stand

on hair- rigger alert. Just last month, Gorbachev made

an urgent plea for actions to prevent a new arms race.

In Hawaii earlier this year, at the height of tensions

between the United States and North Korea, residents

received a false ballistic-missile alert over television,

radio and cellphones. For 38 minutes, many Hawaiians

thought they were about to die. The false alarm reminded

some experts of Cold War-era false alarms, the most

dangerous of which happened late in September 1983—just

two months before The Day After aired. The Soviets’

early-warning system erroneously reported incoming

American nuclear missiles, and the gut instincts and

wise thinking of a Soviet officer, Col. Stanislav

Yevgrafovich Petrov, were all that saved the world from

catastrophe.

In early November 1983—less than two weeks before The

Day After aired, and less than a month after Reagan saw

a preview—NATO conducted a military exercise called Able

Archer, which simulated a nuclear attack and included

flights by aircraft armed with dummy nuclear warheads.

The nonprofit National Security Archive recently

published previously-secret Soviet documents showing

that “ranking members of Soviet intelligence, military,

and the Politburo, to varying degrees, were fearful of a

Western first strike in 1983 under the cover of the NATO

exercises Autumn Forge 83 and Able Archer 83.” (Autumn

Forge, an exercise that airlifted thousands of troops to

Europe under radio silence, culminated with the Able

Archer simulation.) For the first time, the Soviets put

their military on high alert at Polish and East German

bases. Like Col. Petrov, Lt. Gen. Leonard Perroots, the

deputy chief of staff for intelligence at the US Air

Force’s European headquarters, wisely chose not to

respond.

It is not inconceivable that something like the 1983

“war scare” could happen again today. In mid- November,

the Russian military jammed GPS signals during a NATO

military exercise in Norway. CNN called it “the

alliance’s largest exercise since the Cold War.”

In addition to the Able Archer simulation, November 1983

was also the month that NATO began deploying US Pershing

II missiles to West Germany. The missiles were intended

to counter Soviet medium-range missiles capable of

striking anywhere in Europe, and there were huge

protests in Germany over their deployment. It is no

coincidence that nuclear war begins in The Day After

with a gradually escalating conflict in Europe. In one

scene, viewers hear a Soviet official mention the

“coordinated movement of the Pershing II launchers.”

The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty that

Reagan and Gorbachev signed in 1987 resolved that

conflict, banning all ground- aunched and air-launched

nuclear and conventional missiles (and their launchers)

with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers, or 310 to

3,420 miles. However, Trump said in October that he

plans to withdraw from the treaty, and on December 4

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said the United States

would withdraw in 60 days if Russia continues its

alleged non-compliance. Gorbachev and Shultz, in a

Washington Post op-ed published that day, warned that

“[a]bandoning the INF Treaty would be a step toward a

new arms race, undermining strategic stability and

increasing the threat of miscalculation or technical

failure leading to an immensely destructive war.”

The United States first accused Russia of violating the

treaty in 2014, by testing a banned cruise missile, and

later claimed that Russia had deployed such a missile.

However, the United States has not yet divulged details

about the alleged violation, and there are no arms

control talks currently scheduled.

“The one meaningful thing that Trump is doing is trying

to get a dialogue going with Putin,” said former Defense

Secretary (and chair of the Bulletin‘s Board of Sponsors)

William J. Perry at the Bulletin’s annual dinner in

Chicago on November 8. But Russia’s refusal to release

Ukrainian Navy ships and sailors seized in the Kerch

Strait in late November led Trump to cancel a scheduled

meeting with Putin at the recent G20 Summit in

Argentina, where they had been expected to discuss the

fate of both the INF and another treaty for which Reagan

and Gorbachev laid the groundwork in Reykjavik: New

START, which capped the number of nuclear warheads on

deployed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs),

deployed submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and

deployed heavy bombers. Nuclear experts worry that Trump

will let New START expire in February 2021, if only

because it is one of President Barack Obama’s signature

achievements, at which point there would no longer be

any international agreements governing US and Russian

nuclear arsenals for the first time in almost 50 years.

A NEW ARMS RACE

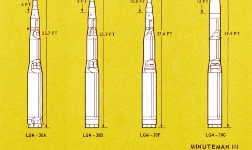

In an October 2017 report, the

Congressional Budget Office estimated that the Obama

administration’s 2017 plans for nuclear forces would

cost $1.2 trillion over the 2017–2046 period.

CBO

When Obama visited the University of Kansas in 2015, he

said nothing about nuclear weapons; he spoke of

middle-class economics and basketball. Although Obama

won a Nobel Peace Prize largely for his vision of a

world free of nuclear weapons, he nevertheless

bequeathed to Trump a 30-year plan to “modernize” the US

nuclear arsenal. Based on a Congressional Budget Office

report, the Arms Control Association estimates that the

United States will spend about $1.2 trillion in

inflationadjusted dollars by 2046 on new bombs, missiles,

bombers, submarines, and related systems. The Trump

administration’s 2018 Nuclear Posture Review calls for a

new generation of land-based ICBMs, which experts such

as Perry view as an unnecessary and risky component of a

nuclear triad that also includes sea- and air-launched

nuclear weapons.

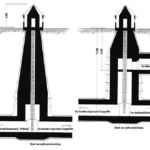

In 1983, the McConnell Air Force Base in Kansas was home

to 18 Titan II missiles, the largest ICBM ever deployed

by the US Air Force. Reagan was proposing to install the

Peacekeeper missile, America’s most controversial ICBM,

in Titan II silos and on mobile transporters. Even

closer to Lawrence was the Whiteman Air Force Base, east

of Kansas City in Missouri, where 150 Minuteman II

missiles were deployed.

In The Day After, Minuteman missiles erupt from the

plains near farmhouses, and people who see the missile

trails above the football stadium and the South Park

gazebo in Lawrence understand that a hail of Russian

ICBMs will soon follow. There is panic in the streets.

When the Russian missiles targeted at Kansas City

detonate during the movie’s extended attack sequence,

flashing brightly and sending up mushroom clouds,

viewers see snippets of footage from actual nuclear

tests interspersed with a horrifying, rapid-fire series

of “skeletonized” people instantly killed in the midst

of everyday activities.

The United States no longer deploys ICBMs near Kansas

City. The force has shrunk by about 60 percent, to

around 400 missiles now deployed near Air Force bases in

Montana, North Dakota, and Wyoming. That’s good news for

the people of Lawrence.

The bad news, however, is that the latest Nuclear

Posture Review calls for the development of new and

dangerous weapons: a new sea-launched cruise missile and

a “low-yield” nuclear warhead that could be more

“useable” than bigger bombs—and arguably more likely to

make military strategists see a nuclear war as winnable

rather than suicidal. The United States might even use

such a weapon in response to a non- uclear threat, such

as a cyberattack. And Trump seems to be as enamored of

his proposed “Space Force” as Reagan was of his “Star

Wars” Strategic Defense Initiative.

The Defense Department claims it needs new weapons to

respond to new threats from Russia, where Putin in 2016

vowed to modernize its own nuclear weapons to “reliably

penetrate any existing and prospective missile defense

systems.” More recently, Putin has bragged about

deploying hypersonic missiles capable of traveling at

many times the speed of sound “in coming months,” and

developing both a global-range, nuclear-powered cruise

missile and an underwater nuclear drone.

The Russians say they have been forced into these

actions by the eastward expansion of NATO and the

installation of missile defense systems in Europe.

Russia is also developing the world’s biggest missile—so

big it could theoretically fly over the South Pole and

avoid US missile defenses.

The rash of new threats makes some experts wonder

whether the United States and Russia are serious about

resolving their differences over the INF Treaty and

other matters—or just looking for excuses to lunge into

a new arms race. “The opponents of arms control have won,”

says Steven E. Miller, director of the International

Security Program at Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science

and International Affairs (and a member of the

Bulletin’s Science and Security Board).

“By the end of the 1990s, we had a nuclear order that

was internationally regulated and jointly managed. Right

now, we're literally on the edge of having nothing left

with regard to nuclear restraint. The case for arms

control has to be fought all over again.”

HOW ACTIVISTS HIJACKED A MOVIE

Louise Hanson, who is now 78 years old, has been pushing

for arms control for most of her adult life. She and her

79-year-old husband Allan, a now-retired professor of

anthropology at the University of Kansas, remember being

terrified newlyweds listening to news of the 1962 Cuban

Missile Crisis on their car radio at night in Chicago.

After they moved to Lawrence, they became leaders in the

Lawrence Coalition for Peace and Justice, a group that

formed in the 1970s and by 1983 was focused on nuclear

weapons. Louise once wrote to her senator, Bob Dole, on

1,000consecutive days, each time giving him a new reason

to halt the nuclear arms race. Today, the Hansons—quick-witted,

gracious, and younger-looking than their years—live in a

tasteful downtown loft one block from the

disaster-struck street that appeared in The Day After.

When

the movie came to town, the Coalition recognized it as a

golden opportunity. Allan and Louise—she played a

“suffering victim” as an extra and elicited a scream

from her high-school daughter when she came home in her

movie makeup—helped create a local campaign around the

movie called “Let Lawrence Live.” They got some

unexpected help from a brash, young media strategist

named Josh Baran, whose only previous experience was

working for the Nuclear Freeze campaign in California.

With a budget of only about $50,000 from the Rockefeller

Family Fund, Baran and Mark Graham (now director of the

Wayback Machine at the Internet Archive) helped make The

Day After a national sensation.

When

the movie came to town, the Coalition recognized it as a

golden opportunity. Allan and Louise—she played a

“suffering victim” as an extra and elicited a scream

from her high-school daughter when she came home in her

movie makeup—helped create a local campaign around the

movie called “Let Lawrence Live.” They got some

unexpected help from a brash, young media strategist

named Josh Baran, whose only previous experience was

working for the Nuclear Freeze campaign in California.

With a budget of only about $50,000 from the Rockefeller

Family Fund, Baran and Mark Graham (now director of the

Wayback Machine at the Internet Archive) helped make The

Day After a national sensation.

Baran and The Day After director Nicholas Meyer had

friends in common in California, and one of them made

introductions. Baran went to Meyer’s house, saw the film

(which was still a work in progress), and took home a

copy. When I interviewed Baran by phone last month, he

said Meyer told him to “do what you want with it, and

don’t tell me.” What Baran did was to create a major

publicity campaign for an ABC movie ... without ABC’s

knowledge or consent. Nowadays this would be called

“hijack marketing”: taking advantage of someone else’s

event to generate publicity for your own cause. But in

1983, “no one had ever done it,” claims Baran, who now

heads Baran Strategies in New York City. “It was a very

far out-of-the-box strategy.”

Baran traveled around the country, stimulating interest

in the forthcoming film among activists and reporters

and planning activities around it. “It took off like

gangbusters,” he recalls. “About halfway through, I told

ABC what I was doing, and they freaked out.” But there

was little the network could do about all the free

publicity they were getting from Baran.

He attributes the success of the movie to several

factors that would be difficult to replicate today. One

was that there were only three television networks in

1983, so programs reached a much broader audience. “I

would not have wanted to make this as a feature film,”

Meyer told the New York Times a week before the film

aired. “I did not want to preach to the converted. I

wanted to reach the guy who’s waiting for The Flying Nun

to come on.”

Retired theater professor Jack Wright doubts that such a

movie could appear today on television. “I think we’re

so politically ostracized now that I don’t know that we

could ever have another event like we had in The Day

After,” he says. “The groups now are so politicized that

they would stop it.”

In 1983, putting the movie on television ensured that it

would spark a national conversation, because it would be

seen simultaneously by millions of people. Bringing the

movie into people’s homes was “was genius really,” says

Louise Hanson, “because it made it much more intimate.”

The Day After also benefited from good timing. Jonathan

Schell’s seminal 1982 book The Fate of the Earth had

awakened readers to the unthinkable prospect of a

nuclear war that would devastate most life on the planet.

The Nuclear Freeze movement was in full swing; a

referendum in Lawrence during the November 1982 election

received support from 74 percent of voters. Nuclear war

was the number one concern preoccupying the nation. The

Lawrence Coalition for Peace and Justice was holding

events around town, like a rally at South Park where

they released “balloons not bombs.” The park appears

briefly in The Day After, with just-launched missiles

visible in the sky above the bandstand. Louise Hanson

says she can’t go by that bandstand, even to this day,

without seeing those missiles in her mind’s eye.

The film did not significantly increase public support

for nuclear arms reductions, but research suggests that

it may have made viewers more knowledgeable about

nuclear war and caused them to think about it more. For

viewers who didn’t want to think about nuclear war,

perhaps the biggest emotional punch delivered by the

movie was the scene in which a husband drags his

screaming wife —who is insisting on making the bed, in a

desperate attempt to maintain normality—to their

basement shelter.

Has it made any difference? That’s what the Hansons

wonder now, 35 years after the movie and the height of

the peace movement in Lawrence, as they play a song by a

local group for me on their living-room stereo: “Uprising,”

the anthem of the local coalition, which has a line that

Louise loves: “I feel it in my bones.” The Hansons find

it alarming that a fictional movie might have played a

key role in changing a president’s views. “We in the

peace movement have been, for decades, dangerously close

to patting ourselves on the head and being satisfied

with consciousness raising,” Louise says. “I see that as

hugely insufficient unless you can translate it into

policy.”

PEOPLE TO PEOPLE

Bob

Swan, Jr., a genial man with warm blue eyes who has

befriended many Russian athletes and met a number of

Russian dignitaries, including Mikhail Gorbachev and

Boris Yeltsin, is hopeful that citizen diplomacy can

fill some of the gaps in policy making. He sees lots of

connections between Kansas and Russia, everything from

the red winter wheat brought to Kansas by Russian

Mennonites, to the American and Soviet soldiers who met

and embraced at the Elbe River in April 1945 on their

way to jointly defeating Nazi Germany. (He proposed and

helped organize a 40th anniversary celebration of the

meetup in Torgau, Germany, for veterans of both armies.)

Bob

Swan, Jr., a genial man with warm blue eyes who has

befriended many Russian athletes and met a number of

Russian dignitaries, including Mikhail Gorbachev and

Boris Yeltsin, is hopeful that citizen diplomacy can

fill some of the gaps in policy making. He sees lots of

connections between Kansas and Russia, everything from

the red winter wheat brought to Kansas by Russian

Mennonites, to the American and Soviet soldiers who met

and embraced at the Elbe River in April 1945 on their

way to jointly defeating Nazi Germany. (He proposed and

helped organize a 40th anniversary celebration of the

meetup in Torgau, Germany, for veterans of both armies.)

A few months after The Day After began filming, Swan

founded the first of several groups dedicated to

improving relations between Americans and Russians. He

called it Athletes United for Peace. The goal was to

promote athletic competition instead of nuclear

hostility. When I visited him in August, the dining-room

table in his home was covered with neatly stacked papers

and memorabilia documenting his persistent efforts

during the 1980s and ‘90s (the University of Kansas

research library has 37 boxes of material from Swan in

its archives). He thought he had “retired” from the

volunteer work that had consumed so much of his time—and

his first marriage—during those years, but now he is

thinking about a possible comeback.

Swan met his current wife, Irina Turenko, in 2002 during

one of several dozen trips he made to Russia. She was in

Russia visiting family when I met Swan at their home,

but he showed me a picture from their wedding day in

2006; he and Irina are standing between an American flag

and a Russian one. Swan had another visitor on the day I

was there: his sharp-tongued fraternity brother Mark

Scott, who speaks fluent Russian and was in Lawrence for

medical treatment. In 1982, Scott came up with the idea

to invite a delegation of Soviet athletes to participate

in the Kansas Relays, a three-day track-and-field meet

that has been held at the University of Kansas every

April since 1923.

Former mayor David Longhurst remembers attending the

1983 reception for the athletes. It was awkward. The

Kansans and the Soviets viewed each other with suspicion.

Longhurst didn’t speak Russian, and the visitors didn’t

speak English. “I was trying to talk to a Soviet shot

putter, and we weren’t communicating at all,” Longhurst

recalls. “I took out my wallet and showed him a picture

of my son. He took out his wallet and showed me a

picture of his kids. All of a sudden, we understood one

another. The barrier just melted.”

The

next day, at the start of the “friendship relays,”

Longhurst told the story to the crowd in his welcoming

remarks. He said it had occurred to him that it would be

wonderful if the leaders of the United States and the

Soviet Union could meet in “a place like Lawrence” and

discover how much they had in common. “The press got

hold of that and went nuts,” says Longhurst. The

headlines said he had invited the two leaders to come to

Lawrence.

The

next day, at the start of the “friendship relays,”

Longhurst told the story to the crowd in his welcoming

remarks. He said it had occurred to him that it would be

wonderful if the leaders of the United States and the

Soviet Union could meet in “a place like Lawrence” and

discover how much they had in common. “The press got

hold of that and went nuts,” says Longhurst. The

headlines said he had invited the two leaders to come to

Lawrence.

Some of his constituents were so enthusiastic about the

idea that they launched a campaign to organize what

became known as the Meeting for Peace. Dole and other

politicians endorsed the initiative. Longhurst and Swan

joined a delegation of schoolchildren (including

10-year-old actress Ellen Anthony) that traveled by

train to Washington to deliver thousands of postcards to

the White House and the Soviet embassy, asking the

nations’ leaders to come to Lawrence.

It took Swan and others more than seven years to make it

happen, but the Meeting for Peace was finally held in

Lawrence and six other Kansas cities in October 1990. By

then, it had become a “people-to-people” event rather

than a summit. About 300 prestigious Soviet citizens

from a variety of regions and backgrounds—including the

son of former Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev— visited

Kansas to attend conferences and art shows, stay with

Kansas families, celebrate the 100th birthday of

Kansas-raised President Dwight D. Eisenhower (a big

proponent of people-topeople exchanges to promote

international understanding and friendship), and “bury

an era” (as a New York Times headline reported). At the

opening assembly, the Kansans and their guests applauded

wildly when it was announced that Gorbachev had been

awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

After Trump’s inauguration, Swan wrote a long letter to

the president and his foreign policy team, proposing a

number of ideas for what he called “a remarkable

opportunity to improve US- ussia relations,” but he

received only a very general reply six months later.

Today, Swan remains hopeful about better relations

between the two superpowers but says “it’s got to be

from the bottom up this time, because our political

system is in such disarray.” He hopes that young people

will lead a fresh effort to improve relations between

Russia and the United States, but it saddens him that “we’vealready

done this.”

A BRIGHT TOMORROW?

In one scene in The Day After, a pregnant woman who has

taken shelter in the Lawrence hospital along with

fallout victims tells her doctor that her overdue baby

doesn’t want to be born. You’re holding back hope, he

says.

“Hope for what?” she asks. “We knew the score. We knew

all about bombs. We knew all about fallout. We knew this

could happen for 40 years. Nobody was interested.”

It won’t be long before another 40 years have passed.

Americans have not yet perished in a nuclear war or its

aftermath, but a new arms race is beginning and the

potential for an intentional or accidental nuclear war

seems to be rising. As Koppel said in his introduction

to the panel discussion that followed The Day After,

“There is some good news. If you can, take a quick look

out the window. It’s all still there.” But, he asked,

“Is the vision that we’ve just seen the future as it

will be, or only as it may be? Is there still time?”

The poet Langston Hughes, who spent most of his

childhood in Lawrence, wrote a line that the city has

adopted as its motto: “We have tomorrow bright before us

like a flame.” It was emblazoned on a banner used by

local anti-nuclear activists for their 1983 campaign.

Today, though, it will take far more than banners or a

movie to awaken a new generation to the risks of nuclear

war, catch the eye of a president, and instigate a

meaningful dialogue between the leaders of the United

States and Russia.

There is hope, though. A year ago, the New York Times

reported that people close to Trump estimate he spends

“at least four hours a day, and sometimes as much as

twice that, in front of a television.” A two-hour film

about ordinary Americans might not interest the

president, but a dramatic twominute video clip of

Washington experiencing Lawrence-style devastation might

get his attention. Especially if it aired on Fox &

Friends.